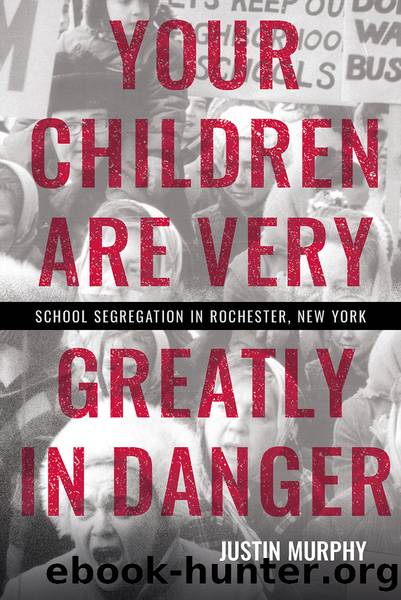

Your Children Are Very Greatly in Danger by Justin Murphy

Author:Justin Murphy

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Cornell University Press

Published: 2021-11-05T00:00:00+00:00

Keyes v. School District No. 1 was finally decided in 1973 in a difficult-to-parse Supreme Court ruling, the first since Brown in 1954 not to command unanimity among the justices. The court found clear evidence of intentional segregation but declined to spell out the standard by which it had done so. It declined as well to address head-on the burning question in northern cities: whether so-called de facto segregation, of the sort seen in Rochester, would be subjected to the same strong medicine as southern-style de jure segregation. For the purposes of Lillian Colquhoun and the Rochester plaintiffs, Denver ended up being much less useful a guidepost than Judge Henderson or other observers had anticipated.60

Meanwhile, continuing demographic shifts in the Rochester area were beginning to make the matter of intracity desegregation obsolete. When the district first tallied its nonwhite students in 1963, they made up 20 percent of the student body. A decade later that proportion had more than doubled. That occurred largely because of in-migration; US Census data showed that the city had a net increase of more than 44,000 nonwhite residents from 1950 to 1970. Equally important, though, was a loss of 80,000 white residents, or one in four, over the same time. They had left the city for the Monroe County suburbs, which registered a net gain of 224,000 residents in that twenty-year stretch. None of those trendsâthe growth of the nonwhite population, the decline of the white city population, and the shifting of the countyâs population base from the city to the suburbsâwere to relent anytime soon. For that reason, even before Keyes was decided, education officials and advocates in Rochester had shifted their attention to litigation in Detroit.61

In the broadest sense, racial segregation of housing and schools in Detroit followed the same pattern as in Rochester. Detroit was an early organizing point for the Black Power movement, and its schools proved to be an important battleground. From 1969 to 1971, Detroit Public Schools suffered waves of violence that made Charlotte Junior High School in June 1972 look like a nursery school picnic. âLiterally hundreds of incidents, including shootings, stabbings, rapes, student rampages [and] gang fights. . . occurred in the schools or school property,â one historian wrote.62

In the middle of a complicated, multiyear fight over community control and desegregation, the NAACP in 1970 filed a lawsuit on behalf of Ronald Bradley and other Black Detroit schoolchildren. Hoping to restore an earlier intracity desegregation plan, it presented evidence to the court of segregative actions not only by Detroit school officials but also by the state of Michigan. The federal court trial judge, Stephen Roth, accepted the plaintiffsâ argument andâfollowing the recent Supreme Court guidance in Green v. County School Board to find a remedy that âpromise[s] realistically to work now and hereafter to produce maximum actual desegregationâârejected proposed Detroit-only desegregation plans, instead issuing an order that would include more than fifty suburban school districts in three surrounding counties. âThe higher courts. . . say when you find segregation you have to go about desegregating,â Roth explained.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Administration | Assessment |

| Educational Psychology | Experimental Methods |

| History | Language Experience Approach |

| Philosophy & Social Aspects | Reform & Policy |

| Research |

The Art of Coaching Workbook by Elena Aguilar(51223)

Trainspotting by Irvine Welsh(21693)

Twilight of the Idols With the Antichrist and Ecce Homo by Friedrich Nietzsche(18643)

Fangirl by Rainbow Rowell(9264)

Periodization Training for Sports by Tudor Bompa(8279)

Change Your Questions, Change Your Life by Marilee Adams(7788)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6894)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5779)

Grit by Angela Duckworth(5623)

Red Sparrow by Jason Matthews(5479)

Paper Towns by Green John(5197)

Room 212 by Kate Stewart(5130)

Ken Follett - World without end by Ken Follett(4740)

Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson(4456)

The Sports Rules Book by Human Kinetics(4399)

Papillon (English) by Henri Charrière(4278)

Double Down (Diary of a Wimpy Kid Book 11) by Jeff Kinney(4278)

The Motorcycle Diaries by Ernesto Che Guevara(4106)

Exercise Technique Manual for Resistance Training by National Strength & Conditioning Association(4076)